“I’m more than what happened to me”

Exclusion. Defined by the behaviour that can be seen, attributed to hidden defects, moved away.

Dr Shawn Ginwright’s 2018 article ‘The future of healing; shifting from trauma informed care to healing centred engagement’ (see footnote) discusses changes over the last 30 years in our approach to serious issues facing young people, to how they behave and respond and how we support them. He quotes one young person as saying “I’m more than what happens to me”. It’s worth thinking about what they meant.

Resilience was promoted in the 1990s as a ‘good thing’ resource children must develop to be able to navigate their pathway and bounce back from adverse, challenging life experiences.

As if it were a new discovery, the UK Government currently urges schools to strengthen children’s resilience as part of character education and a supply industry has grown around this demand. Young people who are deemed insufficiently resilient are seen as a problem to be solved rather than as assets to the community. The rhetoric is that given enough grit and hard work everyone should be able to develop resilience, regardless of the context of their life. Failure to develop a bounce-back ‘growth mindset’ points to their deficit rather than their need for support and the availability of opportunities for healthy development.

At the same time there is a growing awareness of the impact of trauma on children’s learning and healthy development, with numerous initiatives aimed at adopting trauma informed care and trauma informed practices in schools.

How is trauma informed care different to what’s gone before?

Trauma informed care encourages the support and treatment of the whole person rather than focusing on the identification of individual symptoms or specific behaviours. It’s a radical departure from one-size-fits-all strategies of universal consistent practice applied to all children with the aim of achieving their compliance.

How does trauma informed care fit into the current school landscape?

Strict discipline has been advocated in the USA since Canter published the model of behaviour management he called “Assertive Discipline” in 1976. The idea was taken up in the UK in the 1990s and other English-speaking countries including Australia and New Zealand, and promoted as the best way to shape all children’s behaviour into predetermined channels, to train them using behaviourist strategies from the 1930s. Assertive Discipline, rewritten and rebadged as zero-tolerance behaviour management is experiencing a resurgence in the UK. Data-driven school behaviour policies set up the rigid application of the approach, obliterating diversity and difference and treating children as customers of the offer made in school to choose to comply and be rewarded or be punished. Political and school leaders in the UK are funding the spread of this model as the best way to confront ‘disruptive’ classroom behaviour, with exclusion fully integrated into the package and available as the ‘last resort’ when this approach fails to control children. There is no recognition of the effect of adverse life experiences or disability on children’s behaviour and learning and exclusions are on the increase. In one state in Australia in a conference presentation a state administrator described and ‘exponential rise in exclusions for behaviour. Research shows that the act of exclusion itself may add to the harm experienced by previously traumatised children (Bottiani et al 2017 see footnote) but this is not recognised in the course of promoting exclusionary practice in schools.

As an alternative to the Assertive Discipline approach, which marginalises the effects of trauma, some schools are taking a trauma informed approach, offering pastoral support, therapy or counselling to support students’ well-being, assuming that disruptive behaviour is the symptom of a deeper harm rather than wilful defiance or disrespect. A call by the current UK prime minister Mrs. May, in her last days in post, for all schools to have staff trained to diagnose mental disorder continues to place the problem within the child who is struggling in school and characterised as being in deficit of some kind. It allows a culture of segregation by exclusion, within or without school, to remain unchallenged.

Being trauma-informed is vital. Is it enough?

Ginwright suggests that while taking trauma into account in designing practices to support young people in school, the term ‘trauma informed care’ is incomplete.

Firstly, he asserts, it highlights the individual’s specific needs in those young people who have been exposed to trauma. Trauma is located as an individual experience rather than a collective one where research is shown that children who experience of violence in their neighbourhood display behavioural and psychological elements of trauma (Sinha and Rosenberg 2013 see footnote).

Secondly the trauma informed approach ensures the treatment of the individual but does not pay attention to the root causes of trauma in the community.

Thirdly using the term ‘trauma informed care’ risks focusing on the treatment of pathology while sidelining the overarching possibility of well-being and growth. This is made more likely by professionals having been trained in approaches which are aimed at reducing negative emotion and behaviour rather than focusing on building strengths and resources. (Seligman 2011 see footnote).

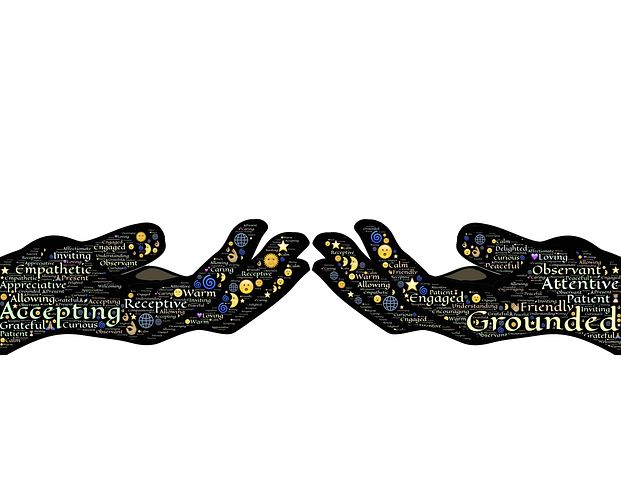

Ginwright offers an alternative view, Healing Centred work; an holistic approach drawing on culture, spirituality, civic action and collective or community healing. Thinking about Healing Centred Engagement (HCE) encourages a more holistic approach to fostering well-being. Healing centred engagement is strengths based, advancing a collective view of healing where culture is a central feature in well-being. It starts with a question ‘what’s right with you?’ in place of ‘what happened to you?’ positioning those exposed to trauma as agents in the creation of their own well-being rather than as victims of traumatic events. Ginwright offers the term Asset Driven Approach aimed at the holistic restoration of young people’s well-being. He offers four key distinctions:

1 healing centred engagement is explicitly political rather than clinical

2 healing centred engagement is culturally grounded and views healing as the restoration of identity

3 healing centred engagement is asset driven, focusing on well-being; what we want rather than symptoms we want to suppress

4 healing centred engagement supports adult providers with their own healing

These distinctions offer a new lens through which we can view school practices.

1 Practices and the theory underpinning them define a school’s approach to behaviour. An authoritarian school, relying on traditional strict external discipline to correct children’s behaviour errors towards an inflexible line and relying on the removal of children who are unable to match up to the standardised model does not offer healing centred engagement. It would be expected that children who have experienced trauma would be reactive to coercive control and over-represented in exclusion figures and indeed this is the case. Schools which are explicitly and (small p) politically organised as communities of healing centred engagement would be expected to avoid the use of exclusion in all forms and this is also true.

2 The radically different orientation of organisation-centred and person-centred schools, either embracing or attempting to eliminate the individual diversity of children. The culture of inclusion means that all children are valued for themselves for what the offer the community as cultural contributors. The culture of exclusion means that only some children, those who confer an advantage on the school in terms of its market performance, are tolerated. Others are ‘othered’ and moved out by one means or another.

3 The approach I have used, taught and advocated since 2001, Solutions Focused Coaching, provides pastoral, preventative support which matches the HCE model – it is asset-driven, focused on well-being in promoting children’s agency and self-motivation and framed by best hopes for the future rather than suppression or correction of past errors.

4 Shifting to the Solutions Focused paradigm means the adult facilitates learning rather than directing it and has no need to be an analytical, diagnostic expert. It follows on that the project of change is co-constructed, a shared enterprise, which enables adults to use the approach with one another as well as with children, as a whole-school cultural practice. It also builds healing centred relationships with parents and carers and others involved in supporting children and celebrating their successes.

Footnote: for references go to: