All you need is love

I have been thinking about how children respond to the messages we, as adults, transmit to them when something goes wrong. In school if we punish them when they cross a bondary, break a rule, make a mistake, mess about, what is the emotional message that we’re sending them as we open the conversation?

How does the use of emotional force play out from their perspective?

If we use physical force to make them comply, what personal meaning might that carry with?

If we make it a battle of wills or of physical strength will the fight, fly or freeze?

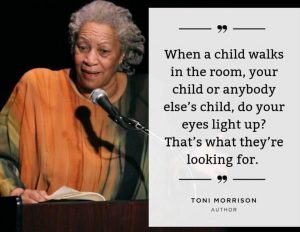

I came across Dr. Natalie Swayn’s (Director of Education, Queensland) Toni Morrison quote on LinkedIn (9 August 2019). The ‘lighting up’ that sets up our relationship happens so quickly and quietly. Does the child know they are loved and respected, they are included? Or do the know the opposite, they’re outside, a member of an other group?

Toni Morrison has a particular way of writing about diversity, segregation and exclusion with a both/and way of looking at these issues as aspects of humanity, without blurring out the destructiveness of discrimination and binary us/them thinking.

It connects strongly with a book I read on holiday this summer, the neuroscientist Dr. Gina Ripon’s 2019 ‘The Gendered Brain’, a highly accessible and up-to-date reflection on neuroscience and neuromyths, their historical roots and current relevance of to educational theory and practice. Ripon presents a reflection on the primary human activity of the social brain and how it relates to the perception of gender, concluding that gender exists on a continuum, with no fixed positions for Male and Female. In building her argument Dr. Ripon places automatic, rapid social communication as the precursor to cognition, laying out the scientific evidence in support of the finding that the brain interprets the social pain of exclusion in exactly the same way as physical pain. For humans, social exclusion is indistinguishable from a physical wound – ‘cut to the quick’ is an appropriate phrase.

Dr. Robert Sapolsky, a neurobiologist, provides more solid evidence in is book ‘Behave – the biology of humans at our best and worst’. Deliberate exclusion is a social act and using it in school to drive changes in behaviour is relying on the pain it causes to drive children into compliance.

When you think about it in these terms it’s no surprise that the fight, flight or freeze responses that children exhibit when they are overpowered and confronted with fear and pain shows up in increasing rates of exclusion. Exclusion may be good for school performance results but hidden in the data is the negative impact on their mental health and wellbeing, their self-esteem and their success in life.

It connects with Dr. Bruce Perry’s ‘The boy who was raised as a dog’, a detailed story in which he draws together the harmful effects of initial and remembered trauma on children’s mental health and wellbeing and no-excuse discipline in schools which sidelines children’s needs and experiences as factors in their behaviour. Dr. Perry, a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, concludes that any intervention for distressed children who are superficially categorised as challenging, non-compliant and disruptive in school, must take as essential first step establishing a relationship of trust and cooperation between adult and child, in which the child can speak and be listened to about their needs, their strengths and hopes. Where all power is in the hands of the adults this doesn’t happen. Flatline, rigidly consistent whole school responses do not allow for it. Talking of some kind is a key part of student support. Research over many years shows that a relationship of trust and kindness is at the heart of all forms of effective talking therapy.

In my own practice of Solutions Focused Brief Therapy in clinical practice and and its sister Solutions Focused Coaching in school, relationship provides the backbone for the work from start to finish, by prioritising the cooperative search for and co-construction of the solutions to a problem rather than the analysis of the problem itself.

These books are stacked with references to work carried out over the last thirty years which has built the foundations for this approach, simplified to the need for the child to experience autonomy, mastery and purpose as they meet problems and reveal solutions , which develops the self-esteem and self-motivation necessary for the child to navigate their life without being collapsed by it.

When your eyes light up as the child walks in, what message does she get about her connectedness, her safety, her sense that those around her are surrounding her with unconditional positive regard as they engage with her hopes for her future? How does the message affect her sense of herself as a person, as an active agent in the world, and how does this in turn affect her mental and physical health and wellbeing?

In her characteristic way Toni Morrison is unconstrained by physical boundaries in talking about this clear and illuminating sense we all have of the automatic and unconscious direct communication between humans. Eyes don’t actually light up but our social brains literally do so, as bursts of neural activity cascade through our physical brain and its virtual equivalent, our social brain.

In my work with children in distress, bringing solution focused brief therapy (SFBT) into my practice, I was struck by the way in which we connected. As an SF Coach and practitioner I hold to the belief that people I meet are hopeful, resourceful and successful. My belief is what underpins my unconditional positive regard for them, not based on case notes or in what other people might tell me about the child who’s about to arrive at the door.

The heart of the solutions focused approach to learning, change and growth – social brains in direct communication. When it comes to forging relationship, all you need is love.